When I was a child my parents didn’t have much money, though we never really noticed as all the other families that lived around us were in the same boat, so we didn’t feel like we were being left behind. There was a particular time when we did feel a bit ostracised and that was when Tony ( my next youngest Brother) and I were at Lawrence Weston School.

You had to queue up to buy a dinner ticket In the mornings from the secretaries office in the main entrance hall. Poor families got free school dinners, and we qualified.

However, you had to stand in a different queue. So on one side you had a line of kids whose parents could pay for their dinner, and on the other side, the poor kids whose parents couldn’t pay.

Now back in the day the kids at Lawrence Weston weren’t the most caring group, there was no such thing as ’empathy’, they ripped the shit out of us. We soon stopped standing in the poor kids queue.

Instead we just went without dinner.

My Dad worked and my Mum stayed home and looked after the three kids ( 4 kids later), cooked and kept the house clean. She was very house proud, cleaning the house from top to bottom every day.

She used to say: ” If we get burgled, I don’t want them (The Burglars) to think we are dirty”!

Not that we had much to steal. Most of what we had was second hand or on HP.

We had Redifusion for the radio and the TV was a small black and white screen set in a huge Oak cabinet that took two people to lift. I think it had a wooden door that we closed across the screen at night but I don’t know why we did that?

My Mum wasn’t much of a cook in the early days, though as she got older she got much better.

We lived on very simple vittles that were delivered by a Grocery van that came all the way from Chew Magna, a village the other side of Dundry Dumps on a Friday evening. Greens were delivered by a Green Grocer with a horse and Cart and the Rag and bone man gave us dead Goldfish for old clothes..

On school holidays my Mum would pack some sandwiches and a ‘glass’ bottle of water (an empty Corona or Tizer Bottle full of tap water) and tell us to walk up to Dundry Dumps where we were to eat our picnic before turning around and walking back home again.

The whole expedition was timed to take a full day.

She would warn us ‘not to stop and eat our food before we got to the top’.

She swore she could see us from the bedroom window and if we stopped, she would know.

The sandwiches were fairly simple affairs.

Often they were ‘Sugar Sandwiches’. Bread and butter with Granulated sugar sprinkled in the middle.

Some times we would get a Pan Yan sandwich. Today that would be a Branston Pickle sandwich. Nothing else, just Pan Yan.

We even had Brown sauce sandwiches.

But on special occasions, (usually a Monday) we would get ‘ Bread and Dripping’.

That was delicious.

“Pork or beef dripping can be served cold, spread on bread and sprinkled with salt and pepper (bread and dripping). If the flavourful brown sediment and stock from the roast has settled to the bottom of the dripping and coloured it brown, then in parts of Yorkshire it is known colloquially as a “mucky fat sarnie”.

Today the thought of giving your children that amount of Fat would be classed as child abuse, but back then it was common fare.

Food was often heavy on stodge and usually fried.

We had fried food regularly. Chips, Sausages, Bacon and Fried Bread were staples.

Fish on a Friday was always fried in batter.

Monday was always left over from Sunday, when we usually, well always, had a Roast.

My Gran would always make the left over into Pasties but my mum would serve the meat up cold and fry the veg and potatoes to make Bubble and Squeak.

Then, we were told that Fat was bad for us.

There wasn’t (as far as I can remember) any recognition of different fats. Fat was Fat and should be avoided if you didn’t want to look like Billy Bunter or die of a Heart attack.

Like many people I changed my diet dramatically.

I developed IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) in my late teens. Mainly because I insisted on smoking too much, drinking too much and eating Curry and Chips late at night.

That usually resulted in the urge for a Pooh during the early hours. But It was too cold to get out of bed and go to the loo (remember, we didn’t have any overnight heating, so once the fire went out, it was freezing) so I would hold it for hours.

One of the side effects of IBS is an intolerance of Fat and I was being bombarded with it.

When my mum made a sandwich the spread was always the same thickness as the bread.

So when I learnt that you could actually eat a low fat diet I was over the moon. I embraced skimmed Milk, Butter substitutes and Mashed potato. I never ate chips or anything fried for years. probably in my early 50’s I started to relax and eat more fatty foods.

My first day on Training School I joined the Fire Brigade they asked if anyone had dietary needs. I of Course said I didn’t eat Fat.

“I see, probationary Fire Fighter Hendy”. They said very sympathetically.

“Well, we have two choices for you. Eat it or go without”.

They insisted on serving me Cheese salad with Chips for the first Month!

Don’t you just love the uniformed services?

When I met my First wife I went to stay with her in Hungerford where she lived and she made us Bacon and Egg Sandwiches on the Sunday Morning, using Poached Eggs.

I had never seen a Poached Egg in my Life.

Even the stain on my Mums bedroom wall was caused by a Fried egg when she threw the breakfast plate at my Dad in one of her rages.

As time went on we all changed our diets, moving to a lower fat diet was a national obsession and the range of diet or low sugar, low fat foods grew larger as the food industry realised there was money to be made.

High Cholesterol became the norm for anyone over 13 and more and more of us started taking Statins and other medication to reduce our cholesterol levels and control High Blood Pressure.

Doctors constantly told us we should reduce our fat intake or we would die prematurely.

I remember in the early days of the Cholesterol revolution that Americans were eating Omelette made with egg white as the Yolks contained too much Cholesterol.

Then the bubble burst. Coinciding with the internet and access to Professor Google, we were able to look up things for ourselves. To research things or listen to alternative views.

Now, where is all this leading?

Well it’s all about Ghee.

For those that don’t know:

‘Ghee is a variation of clarified butter that is popular in the culinary traditions of the Middle East and India. How is ghee made? It’s made from cow milk butter, treated with low heat until the water evaporates, leaving milk solids behind. The solids are skimmed off or strained if needed. Ghee and clarified butter are similar, but there are differences in how you make them. The process starts the same, but with ghee, you cook the butter a bit longer, which turns the proteins golden brown and creates a toasted aroma. You create ghee by removing milk solids. Because of this, it has only trace amounts of lactose and casein, which are milk sugars and proteins. Ghee is a good source of fat for people who are lactose intolerant or have dairy allergies’.

Those of you who follow my wittering rambles on a regular basis will know I have been on a quest to eat healthily for the last 6 months.

It started when my weight went up to 100 kilos and Frazer, Georgias partner told me he was going on a Low Carb Diet. I decided I would try it too and quickly got into the swing, reducing my carb intake and my weight considerably.

As is quite common these days, I started looking on line for Keto tips ( the Keto diet is a form of low carb or maybe high protein diet) and meals that would help me manage my diet.

I soon discovered a range of Influencers that examined food and made recommendations about what to buy and what to eat as well as how to cook food.

After a while my diet changed from a Low Carb diet to a Healthy eating diet.

By now I had lost 8-10 Kilos and although I would like to lose a few more, I had the luxury of being able to relax the diet and eat reasonably flexibly.

In the early stages I avoided pasta, Rice, Bread and Potatoes like the plague but now I eat them, in moderation. But there are tricks. For example:

If you cook Potatoes (boil them) at night, then leave them in the fridge over night the ‘Healthy food Fairy’ visits and does her thing. Then, if you cook the potato the next day, even fried, some thing magic has happened to them and they are less fattening.

It’s some thing to do with chemicals changes that take place in the fridge which makes the Potato a ‘Resistant Starch’. That means it’s digested differently and serves as a food for the friendly bacteria in your gut. They alkalise which is apparently good for you.

Who Knew?

There is also another Magic bullet and that is Coconut Oil. (I’m ignoring Extra Virgin Olive Oil for now as most of you are familiar with its healthy reputation).

You use it to fry food, like you would use butter but it has some strange properties that affect the food and make it behave differently in your body.

It is suggested you put a teaspoon of Coconut Oil in the water when you cook rice. This changes some thing (way too technical for me to go into here) and reduces the calories when you eat it. How the Ferk it does that, I don’t know but I do know it makes great Sourdough fried bread!

These Magical revelations kept on coming.

I learnt that Butter wasn’t the Demon it was made out to be. It is actually healthier than the low fat substitutes I had been eating like Olivia and Flora which contain a whole host of nasties required to make it taste remotely edible.

When you look at the ingredients of these Butter substitutes you start to see the warning signs.

Sun flower Oil.

Sunflower oil and other industrial seed oils are responsible for a massive increase in the intake of omega-6 fats, which are linked with inflammation, obesity, heart disease, cancer, and other health issues

Canola Oil

Some studies suggest that canola oil may increase inflammation and negatively impact memory and heart health. However, other research reports positive effects on health including the possibility that it might lower LDL cholesterol.

Palm Oil.

About 50% of palm oil is made up of saturated fat, mainly palmitic acid. High intake of this type of fat can increase blood LDL or ‘bad’ cholesterol levels, boosting cardiovascular disease risk. Also, like all oils, palm oil is packed with calories and moderation is key.

Take a look at the longer version of Palm oil at the end of this blog, if your not already asleep.

One of the best bits of information I came across related to Ghee the buttery stuff they use in Indian restaurants. In the old days I would scoop that fat off the top of my Curry and pour it down the drain. good for my heart, bad for the drains right?

Well it turns out Ghee , like Coconut Oil is Magic and can make unhealthy food healthy. Well, not literally but you get my meaning.

So I went on a mission to buy some Ghee.

The first thing I realised was that it was bloody expensive and in general, hard to find.

Imagine my surprise when I found a huge tub of it in a small shop on the Gloucester Rd and it was only £7 (ish).

I bought it and carried it home like the wise man carrying Myrrh for the baby Jesus.

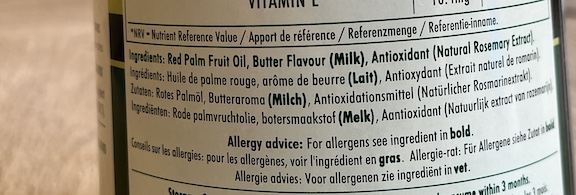

However when I got home and put my glasses on I was able to read the label clearly. This wasn’t Ghee it was some sort of Vegetarian alternative. It said it was healthier but I was suspicious so I read the label.

The ingredients were:

Red Palm Oil which immediately set alarm bells ringing.

Butter Flavour (Milk). What the hell is that?

Antioxidants (Natural Rosemary Extract).

This was a dilemma. It wasn’t clarified Butter but it didn’t have a list of emulsifiers, colouring and additives either.

So, I am using it and I have to say it cooks fine, tastes fine but whether its really good for me, or good for the planet, remains to be seen.

I can tell you It makes great Fried Bread and if you compare the calories to buttered toast, It isn’t too bad.

So here’s the thing.

When you look at food you really need to be on top of your game or you can easily poison yourself. Don’t believe it when a drink says it has no sugar because they simply call it some thing else.

Don’t buy crap food. Don’t buy food that has been messed about with or adulterated with unknown ingredients.

I went to visit my Gran once and she made sandwiches for me and my Mate ‘Potter Yandell’.

As she was carrying the tray of food, she slipped and all the pickled onions rolled on the floor. She picked them up, wiped them on her Piny and put them back in the dish.

If we hadn’t have seen it, we wouldn’t have known?

So, were those Onions bad for us?

I don’t know but I can tell you, hairy pickled onions are an acquired taste!

—————————————————–000000—————————————————————-

Unrefined palm oil is sometimes referred to as red palm oil because of its reddish-orange color. The main source of palm oil is the Elaeis guineensis tree, which is native to the coastal countries of West and Southwest Africa, including Angola, Gabon, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and others.

The Production of Red Palm Oil

RPO

Red palm oil (RPO) is extracted from the mesocarp of the oil palm fruit. RPO is obtained through a modified physical refining process.

Unlike crude palm oil (CPO), The process consists of pre-treatment of CPO by degumming and bleaching, followed by deodorization and de-acidification. During pre-treatment stage, CPO is treated with phosphoric acid and subsequently treated with bleaching earth followed by filtration. The oil is then de-acidified and deodorized through molecular distillation at low temperature and pressure (Choo et. al, 1995).

Apart from the physical refining method, RPO can also be obtained through a modified chemical refining process. This process involves pre-treatment of CPO as mentioned above, followed by deodorization at low temperature (Affandi et. al, 1995).

Phytonutrients in RPO

The processing of RPO preserve about 80% of the carotenes and vitamins present in CPO (Ooi et.al, 1991). Thus it is rich in phytonutrients such as carotene (that gives the oil a brilliant red colour), vitamin E, phytosterols, squalene and coenzyme.

RPO is one of the richest natural plant sources of carotenoids which are naturally occurring as fat-soluble pigments. They are the most widely distributed pigments in nature and are the source of yellow, orange and red colours in many plants. They can be broadly classified as carotene and xanthophylls.

Vitamin E is an important antioxidant and confers stability against oxidative deterioration of the oil. Compared to RBD palm oil, more than 80% of vitamin E present in CPO is retained in RPO

RPO is being used in salad dressing, curries and sauces (Unnithan and Choo, 1996). RPO can also be used to make margarine by giving the required colour and the desired level of provitamin A. RPO is also ideal for stir frying, since most of the carotene is retained in the cooked foods (Choo, 1993). Apart from that, RPO has also been used in shortenings, vanaspati, cake mixes, breads, biscuits and also health foods.

Health Benefits of RPO

At present, though most of the valuable minor components of CPO are retained in RPO, the nutritional potential of RPO is underutilised. RPO supplementation could be a practical and economical approach to address vitamin A deficiency and other health problems such as cancer, diabetes, infections and cardiovascular-related complications. To date, most studies were animal-based. Further clinical studies are needed to support the growing evidence that RPO can be a useful and healthful addition to the human diet.

- Improves vitamin A and antioxidant status 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

- Prevention of cancers 6, 7, 8

- Beneficial against atherosclerosis 9

- Positive effect on immune function 10, 11

Mike Shanahan is a freelance writer and journalist, specialising in environmental issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss

To say that palm oil is divisive is an understatement. To its advocates, it is a cornerstone of economic development, making efficient use of land and supporting millions of smallholders through profitable international trade. To its detractors, it is a cause of deforestation and social conflict, a direct threat to endangered species and a contributor to climate change.

As demand for palm oil continues to rise, there is growing concern about its sustainability and awareness that some palm oil is “good” and some is “bad”.

What is palm oil?

The term covers various things we get from a species of tropical palm called the African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis). “Crude palm oil” is squeezed from the palm’s fleshy red fruit, while “palm kernel oil” is extracted by crushing the fruit’s hard seed. Finally, many “palm oil derivatives” are acquired through industrial processes, which together account for about 60% of global palm oil use.

Where does palm oil come from?

The oil palm is native to West Africa, where its relationship with humans goes back thousands of years. However, its profitability was realised in Southeast Asia, when appropriation of oil palm by colonial companies established the first plantations that have now expanded to dominate landscapes. Today, about 83% of all palm oil comes from Indonesia and Malaysia. More than 40 other countries produce it, in far lower but fast-increasing quantities. Thailand accounts for 4% of total production, while the top producers in South America and Africa are Colombia (2%) and Nigeria (2%).

Oil palm is something of a wonder crop. It yields 4-10 times more oil per hectare than other sources of vegetable oil such as soybeans or coconut palms. The plant accounts for just 9% of the 322 million hectares of land used to produce oil crops globally, yet it produces 36% of the oil. This makes it an efficient and profitable use of land. The economic value of palm oil translates into jobs, infrastructure and tax revenues.

Why is palm oil so controversial?

Where to start?

The palm oil rush of recent decades – there has been a seven-fold increase in production since 1990 – has come at considerable cost to forests and people who depend on them.

This has also had direct consequences for climate.

⚪ Social impacts: Palm oil production has been associated with corruption, forced evictions and land-grabbing. It has sparked conflict with local communities, including indigenous peoples. There have been serious concerns about forced labour, child labour and violations of worker rights on some plantations including low wages, intimidation and sexual harassment.

There has been a lack of meaningful inclusion of smallholder farmers in the palm oil supply chain, even though they contribute around 40% of production. Pollution of air from forest fires and water from plantation run-off has also harmed human health.

⚪ Harm to forests and biodiversity: Oil palms now cover a combined area about the size of Syria, and 45% of oil palm plantations in Southeast Asia are on land that was still covered with forest in 1989. Much of the deforestation has been in Indonesia and Malaysia, destroying the habitat of rare species such as orangutans, tigers, rhinos and elephants. As expansion for oil palm plantations takes place in new frontier regions in Latin America and West Africa, the threat to standing forests remains.

⚪ Climate impacts: Deforestation, degradation of peatlands and associated fires all contribute to climate change. According to a 2018 study, replacing rainforest with oil palm plantations releases 61% of the carbon stored in the forest, mostly into the atmosphere. Each hectare of rainforest converted releases 174 tonnes of carbon.

How big a problem is this?

The ubiquity of this commodity and the growing demand for it highlight the scale of the challenge. Between 2000 and 2015, the global average amount of palm oil consumed per person each year doubled to 7.7 kg. And with global demand for palm oil set to rise from 76 million metric tonnes today to an estimated 264–447 million by 2050, it’s clear that the way we produce and consume palm oil needs to change if the industry wants to do more good than harm in the future.

Should we just ban it?

No. That could have disastrous effects. It would negatively affect the livelihoods of millions of people, and producing alternative oils would require even more farming land. If the world’s entire supply of vegetable oils came from palm oil, we’d need 77 million hectares of land. If it came solely from sunflower oil, on the other hand, we’d need more than four times the amount of land (312 million hectares). Environmental organisations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature say that, instead, we need to prevent further deforestation for new oil palm plantations and focus on promoting sustainable production.

It is not easy, for a couple of reasons. First, many products contain palm oil but their labelling does not make this clear; palm oil derivativeswith names like sodium lauryl sulfate or propylene glycol are listed in the ingredients. Second, the complexity of palm oil supply chains mean it is not easy to trace these ingredients back to the land on which the oil palm fruit was harvested. This makes it hard to tell if palm oil comes from plantations that have deforested land or infringed local people’s rights.

What about eco-labels?

Various schemes certify companies and/or supply chains as “sustainable” if they meet certain environmental and social criteria. These schemes use different standards and means of verifying performance, and some leave much to be desired. Some producer countries like Indonesia and Malaysia have introduced their own standards for sustainable palm oil production. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is widely recognised as the strongest standard. However, about one-fifth of globally traded palm oil is certified by the RPSO – and it isn’t always labelled as such.

RSPO faces challenges of post-pandemic palm oil

Some producers are going further than certification, electing to adopt regenerative farming and organic practices. These methods centre on the importance of soil vitality, encouraging a more diverse farming system through inter-cropping and using organic wastes as fertilisers. Though these practices are far from being applied at scale, the early adopters are paving the way for transforming the sector.

So, is certified palm oil really sustainable?

Some academics and non-governmental organisations say certification standards and audits are too weak or, worse, that they greenwash the damage companies do. Others say that in the absence of stronger national laws and regulation, certification is the best tool for reducing the harmful impacts of palm oil production. There is no doubt that the RSPO has galvanised change through improvement of industry practices. But with legislative changes from the EU, UK and USshifting palm oil sustainability from a voluntary to a mandatory space, the existing certification structures within the sector are likely to evolve.

Is palm oil still driving deforestation?

Yes and no. Palm oil has certainly played a part in global forest loss and for that the sector has received heavy scrutiny. But a study published last year found that deforestation in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Papua New Guinea attributed to plantation development has fallen to its lowest level since 2017. Another study showed that in 2018–2020, deforestation for palm oil in Indonesia was 45,285 hectares per year – only 18% of its peak in 2008–2012. The widespread adoption of zero-deforestation commitments and efforts to increase transparency within the sector are believed to have contributed to this trend.

How does palm oil compare to other commodities?

It is important to think about palm oil in relation to other soft commodities. Every year, the world loses around 5 million hectares of forests, and about 80% of this is driven by agricultural expansion for producing commodities.

‘Forest-risk commodities’ are those that may contribute to tropical deforestation and degradation. They include, but are not limited to, cattle (for beef and leather), soy, palm oil, cocoa, timber, maize, coffee, rubber, paper and pulp.

In consumer markets influenced by anti-palm-oil campaigning, the perception that palm oil drives deforestation has stuck. But if we truly want to tackle global deforestation, we need to expand our understanding of the what, where and why of global forest loss.

Expanding pasture for cattle grazing is by far the greatest agricultural threat to forests and climate

Palm oil is certainly still a contributor to forest loss, but expanding pasture for cattle grazing is by far the greatest agricultural threat to forests and climate. In 2021, deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon reached their highest level in 15 years, with nearly three-quarters attributedto expanding pasture. Meanwhile, soy production, 77% of which is fed to livestock for meat and dairy production, has contributed greatly to forest loss in the Amazon. However, the introduction of Brazil’s ‘Amazon Soy Moratorium’, which aims to limit the production of soybeans on recently deforested lands, has effectively shifted the deforestation into other important ecosystems like the vast tropical grasslands of Brazil’s Cerrado.

Meanwhile, rubber production is an emerging threat to west and central Africa’s climate-critical tropical forests. A recent analysis has found that 52,000 hectares of natural forests were cleared to establish rubber plantations between 2000 and 2020 across Cameroon, Gabon, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Liberia.

So how do we end deforestation?

This really is the question of our time. Thankfully, global society is recognising that we cannot address the climate crisis without ending deforestation, which accounts for 15% of global carbon emissions. This took centre stage at the 2021 UN climate talks in Glasgow when 141 countries committed to reversing forest loss and land degradation by 2030. This reinvigorated existing commitments made under the New York Declaration on Forests back in 2014.

While international cooperation is crucial, corporate commitments are also essential. The palm oil sector has made more progress in addressing deforestation than other commodities have. An analysis by Forest 500 found that 72% of palm oil companies have deforestation commitments, but other commodities like pulp and paper (49%), soy (40%), beef (30%) and leather (28%), have much lower commitment levels. A meagre 28% of companies have commitments for all of the commodities associated with deforestation in their supply chain.

The EU, as the second largest market for forest-risk commodities after China, has adopted legislation requiring mandatory due diligence for companies connected to these commodities. In short, companies will have to prove their products are not linked to deforestation. While some argue that it falls short on human rights issues and could alienate small-scale farmers, the legislation is a holistic approach to addressing interconnected challenges we face as a global society – particularly sustainable development, food security, ensuring livelihoods, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

This kind of holistic regulation can raise awareness among consumers and companies, pushing change across the board. But solutions must also include reforestation programmes, sustainable land-use practices, and effective protection of the forested areas that remain.

Simultaneously, and perhaps most importantly, we need also to address the root causes of deforestation: demand for food and biofuels, overconsumption in wealthy nations, changing diets, and weak land tenure systems that undercut Indigenous customary land owners.

.

Continue reading